Rosalind Williams, Dream Worlds -- Visions of the Exotic

Distant Visions-For all its innovation in stylistic absurdity, the exotic-chaotic decorative style was traditional in its technology. Its only technical novelty involved the use of increasingly convincing imitation materials to construct "all those domes, balconies, pediments, columns." Nineteenth-century technology developed far more effective ways of creating an illusion of voyage to far-off places, techniques that were dynamic and cinematic rather than static and decorative. They proved so exhilarating and popular that while occasionally used to publicize products, they more often became products themselves, offered as amusement attractions. At the 1900 exposition twenty-one of the thirty-three major attractions involved a dynamic illusion of voyage. This group of exhibits, like the colonial ones clustered at the Trocadéro, furnished a "lesson of things" in the form of a scale model of a dream world of the consumer.

As Maurice Talmeyr enunciated the lesson of "the school of Trocadéro," so another journalist, Michel Corday (Louis-Léonard Pollet 1869-1937) assessed the significance of the exhibits providing "Visions Lointaines" ("Distant Visions" or "Views of Faraway Places"). This is the title Corday gave to an article on cinematic exhibits one of a series he wrote on the exposition- published in the Revue de Paris. Corday was well able to appreciate these exhibits from both a technical and a cultural perspective, for he had been educated as an engineer and served with distinction in the army before deciding, at the age of twenty-six, to devote himself to letters. The imprint of Corday's technical training is manifest when he begins by classifying the twenty-one "distant visions" exhibits into five categories, according to the increasing sophistication of the techniques used to convey the illusion of travel: "ensembles in relief" panoramas in which the spectator moves, those in which the panorama itself moves, those in which both move, and moving photographs. One of the more primitive exhibits, an example of the second category, was the World Tour: the tourist walked along the length of an enormous circular canvas representing "without solution of continuity, Spain, Athens, Constantinople, Suez, India, China, and Japan," as natives danced or charmed serpents or served tea before the painted picture of their homeland. The visitor was supposed to have the illusion of touring the world as he strolled by, although Corday hardly found it convincing to have "the Acropolis next-door neighbor to the Golden Horn and the Suez Canal almost bathing the Hindu forests"-the chaotic-exotic style, the universe in a garden, only on canvas! On a somewhat more ingenious level, the Trans-Siberian Panorama placed the spectator in a real railroad car that moved eighty meters from the Russian to the Chinese exhibit while a canvas was unrolled outside the window giving the impression of a journey across Siberia. Three separate machines operated at three different speeds, and their relative motion gave a faithful impression of gazing out a train window. A slight rocking motion was originally planned for the car, but the sponsoring railway company vetoed the idea because it advertised that its trains did not rock.

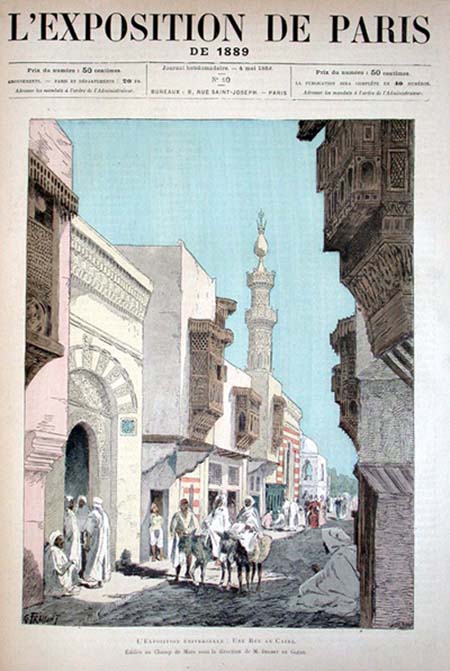

Reconstruction of a Street in Cairo at the 1889 Paris Exhibition

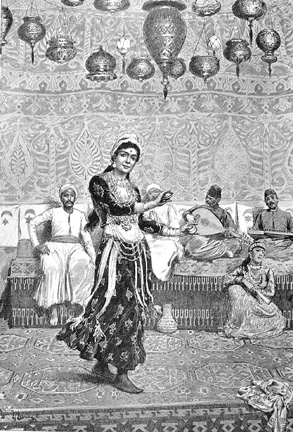

Dance at Egyptian Cafe, Cairo Street, 1889 Exhibition, Monde illustre

The Pavillion of Electricity at Night at the 1900 Paris Exhibition

Corday was even more intrigued by an attraction where not canvases but photographs moved:

This is Cinéorama, the application-it is surprising that it did not appear sooner-of cinematography to the panorama. This ingenious apparatus . . . is placed in the center of the spectacle to be reproduced .... [T]he projector is composed of ten cameras which work in unison and divide the horizon into ten sections, like ten slices of cake.

The Cinéorama could convey the impression of ascending from the earth in a balloon, by a series of panoramic photographs showing things below growing smaller and smaller. To make the illusion even more persuasive, spectators stood in the basket of a balloon to watch the show . Finally, Corday describes some exhibits appealing to many senses at the same time. The Maréorama reproduced a sea voyage from France to Constantinople, complete with canvas panorama, the smell of salt air, a gentle swaying motion (unlike trains, boats were expected to rock), and phonograph music "which takes on the color of the country at which the ship is calling: melancholy at departure, it ... becomes Arabic in Africa, and ends up Turkish after having been Venetian."

Even sailing to Byzantium was not enough: the surface of the earth was too small to contain human imagination armed with such gadgetry. Corday marvels that new devices allow the masses to realize the "extraordinary voyages" of Jules Verne, to travel not only where few have ventured but also where none have. The Cinéoramatic balloon trip was only the first step in flight from earth bound reality. At another exhibit a diorama took the tourist far beneath the earth to dramatize its formation by showing vast subterranean and prehistoric landscapes strikingly lit by electricity. In the Optical Palace photographic plates were pieced together to give the impression of viewing the moon from a distance of only four kilometers. Then, according to Corday, the diorama makes its appearance; at first prudent, it reproduces with exactitude the lunar landscape: then, fan tastically, it paints an imaginary voyage to a star; finally, leaping across centuries as easily as space, it narrates the genesis of the earth in twenty tableaux.

So convincing was this illusion that the spectator was hardly aware of crossing the line between reality and fantasy, of moving from a painstaking reproduction of the moon's surface to a wholly imaginary simulation of a journey beyond the galaxy. Real and fantastic voyages, present and future and prehistoric ones, earthbound and cosmic ones became indistinguishable when all were presented as triumphs of technical ingenuity.